Complex numbers#

“Life is complex sometimes”

Unknown author

Typically, the spirit of the Elara handbook is to present all the ideas of a topic at once, without a lot of prior background knowledge. However, for quantum mechanics, it is especially good to get a grasp of complex numbers, because the use of complex numbers often makes the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics foreign and indecipherable. So dive in, enjoy, and let’s see how an mathematical idea that was once said to exist “only in our minds” would turn out to be one of the most invaluable tools to solve real-world problems…

Imaginary and complex numbers#

Say we were struggling with a problem. In fact, a very peculiar problem. Suppose that problem was:

How could we solve this for \(x\)? Using the usual algebraic methods, we immediately hit a roadblock:

But surely that does not make sense, you say! You cannot take the square root of a negative number, certainly! Or can you…?

Indeed, the above equation does not make sense in terms of the numbers we are familiar with, called the real numbers, and denoted with \(\mathbb{R}\). However, we can define - or perhaps, to use a more artistical term, imagine - a set of numbers for which this equation does make sense. We therefore define:

We can then create a system of numbers, which we term imaginary numbers, based on \(i\): \(2i\), \(3i\), \(\pi i\), \(1.52434i\), \(\frac{3}{4}i\). And we can go further! We can even create a system of numbers that contains both real numbers and imaginary numbers, such as \(3 + 4i\), \(5 + 6i\), or \(9 - 2i\). We call these complex numbers. A complex number \(z\) is defined by:

The real and imaginary parts of the complex number \(z\) are:

Complex numbers can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided just like real numbers. Other than containing imaginary parts as well as real parts, they may well just be considered ordinary numbers.

The complex plane#

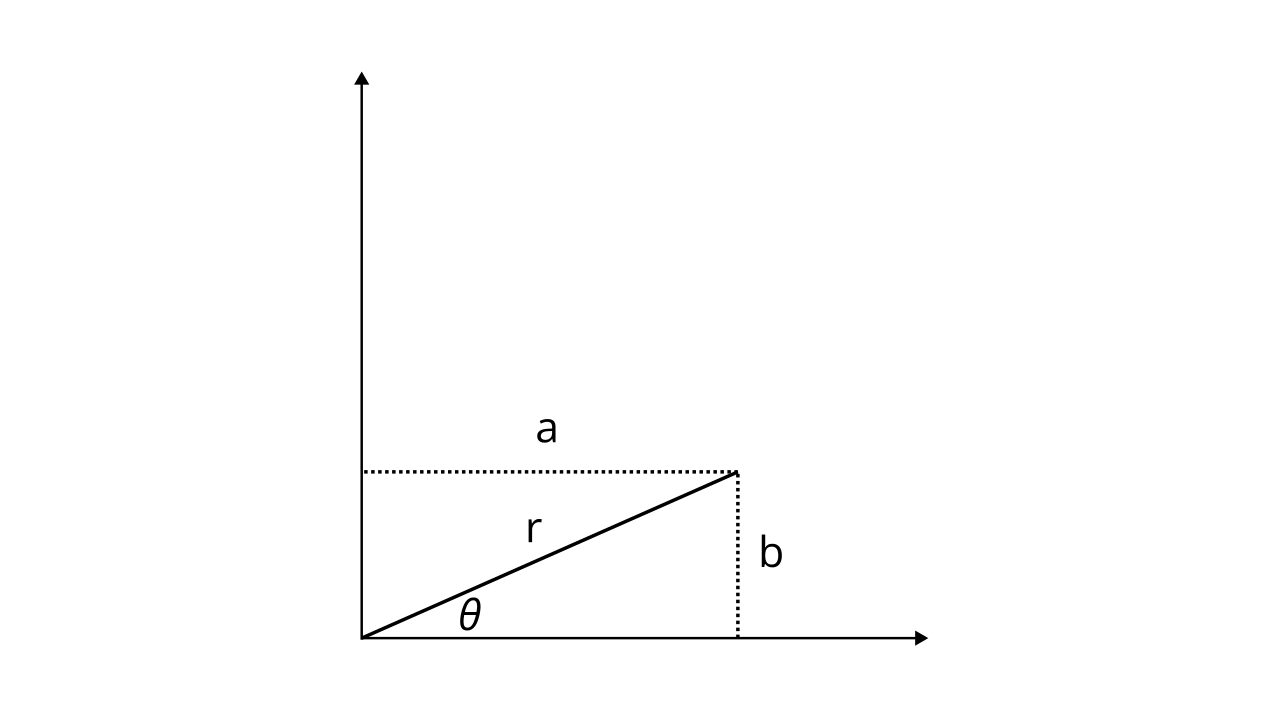

But what makes complex numbers so…different? Perhaps one way of thinking about them is that they are two-dimensional numbers. Yes, you heard that right, not two dimensional vectors - two dimensional numbers. We can draw out complex numbers by plotting their real part on the x-axis and imaginary part on the y-axis, to get the complex plane:

Here, notice that \(r = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}\), and that thanks to trigonometry, \(a = r\cos \theta\) and \(b = r\sin \theta\). If we take the complex number formula, and substitute the identities, then we have:

If \(r = 1\), then:

This is called the polar representation of complex numbers.

Euler’s formula#

We already know from the polar representation of complex numbers that any complex number \(z = a + bi\) can be written as:

If we were to take the derivative of \(z\) with respect to \(\theta\), we’d get:

Now, this is interesting, because unlike many derivatives, we can actually write the right-hand side of this equation in terms of \(z\):

We can solve this differential equation, like we did for other differential equations earlier in this book. First, separate the variables:

Then, integrate to get:

We can take the exponential of both sides to get:

Now we just need an initial condition, \(z(0)\). But we know that:

So, \(z(0)\) would be:

Using our initial condition \(z(0) = 1\), we can now solve the differential equation exactly:

And remember, since \(z = \cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta)\), we can substitute that in to get:

This is Euler’s formula. Note that when \(\theta = \pi\), we have:

Which we can simplify to:

This is Euler’s identity, one of the most famous equations ever, showing that two previously completely unrelated ideas, those being trigonometry and exponentiation, are actually linked. You’ve got to appreciate Euler’s skill as a mathematician after looking at this equation, and wonder if the true genius was Euler, not Einstein.

Complex conjugation#

If we have an imaginary number \(a + bi\), it turns out that if we multiply that by its complex conjugate \(a - bi\), we get a real number:

This is because by definition, \(i^2 = 1\), so \(-b^2 i^2 = -b^2 (-1) = b^2\).

Complex waveforms#

Using Euler’s formula, we can write waves in terms of a function of \(e\) rather than using sines and cosines:

Why do this? Exponentials are far, far easier to differentiate and integrate than sines and cosines, and so writing out waves in this form allows them to be more easily expressed in quantum mechanics, which involves hoards of derivatives and integrals.

Before we finish this short chapter and jump into quantum mechanics, there is one last fact about complex numbers that is trivial, but confuses a lot of people. That fact is that:

Remember this fact, and we will meet you again in quantum mechanics!